Indigenous rights and public lands: A chat with Anna Elza Brady

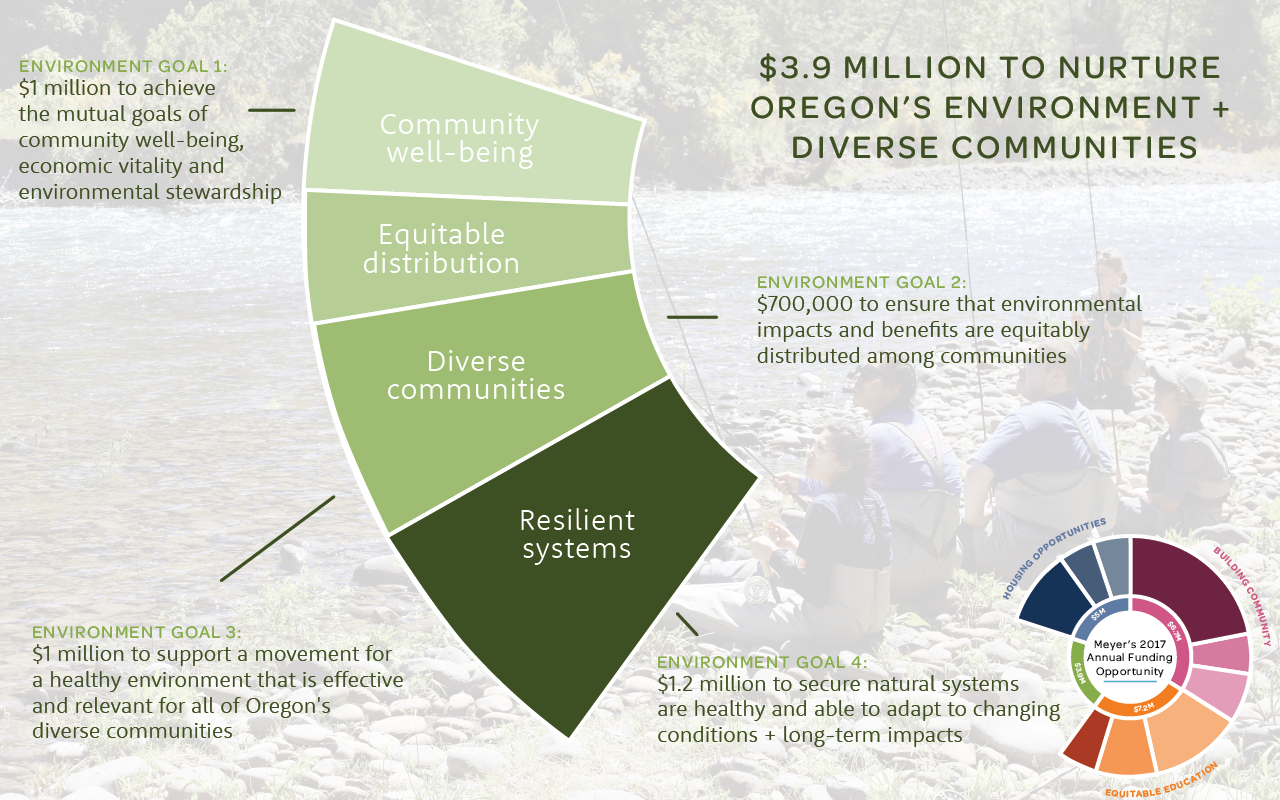

A key goal of the Healthy Environment portfolio is to support a movement for a healthy environment that is effective and relevant for all Oregon's diverse communities. So we were delighted to have a chance to speak with Anna Elza Brady, an advocate who works to elevate the voices of people and place. Next month, Anna will be speaking on a panel titled “Decolonizing Public Lands” at the University of Oregon Symposium on Environmental Justice, Race and Public Lands. I recently caught up with her to get a preview of thoughts she will share on the panel on Friday, May 11.

Jill Fuglister:

Can you please share a little about the coalition of tribes that have led the Bears Ears protection effort and why this place is important to them?

Anna Elza Brady:

From the outset, the effort to protect the Bears Ears cultural landscape as a national monument was developed by elders and local Native American grassroots citizens and later led by a historic coalition of sovereign tribal nations. Five tribes — the Navajo Nation, the Hopi Tribe, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, the Pueblo of Zuni, and the Ute Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation — came together as sovereigns in 2015 and, with a unified voice, called on the president of the United States to designate 1.9 million acres of shared ancestral homelands in southeast Utah as Bears Ears National Monument.

As I have heard expressed time and again by tribal leaders and elders, the Bears Ears cultural landscape is important to the five tribes because it is the dwelling place of the spirits of the ancestors. For those peoples who have inhabited these lands since time immemorial, the spirits of the ancestors are still very much alive in the Bears Ears landscape. When tribal members travel within Bears Ears, they are visiting those who have come before, who walked these lands, harvested its foods and medicines, and left their stories etched in rock. Archaeologists estimate there are over 100,000 cultural and archaeological sites within Bears Ears National Monument — the densest and most well-preserved concentration of such sites anywhere in the United States. For the coalition of tribes that led the effort to protect Bears Ears National Monument, these sites are not simply objects of study: They are the resting places of the Ancient Ones. In this way, the Bears Ears region is sacred and must be safeguarded accordingly.

Bears Ears is also important to local people because it serves as a key source of essential natural resources, including firewood, medicinal herbs and food plants such as pinyons. In the arid desert southwest, Bears Ears is a sort of island ecosystem, providing habitat for a variety of plant and animal species, many of which are not found elsewhere in the region. Jonah Yellowman, a Navajo elder and spiritual leader who has lived in and around the Bears Ears region since birth, explained to me in 2014 how Bears Ears is “our grocery store; it’s our pharmacy.” Jonah also taught me about nahodishgish, the Navajo word for wilderness, meaning literally “places to be left alone.” Nahodishgish recognizes that some landscapes are meant to be used by human beings and others should remain as they were created: untrammeled places from which wild life emerges. Native peoples of this region know that the Bears Ears landscape — the rugged terrain of canyons and mesas fanning up from the sacred confluence of the Colorado and San Juan rivers — is a place of healing and renewal for all people and all beings.

Jill:

In what ways is their organizing approach different than other national monument/public lands protection organizing efforts, particularly those led by mainstream environmental organizations?

Anna:

The tribes’ organizing approach around Bears Ears National Monument has been fundamentally different than other public lands protection efforts, in part because of tribal peoples’ profound history and depth of relationship with these lands. The tribal leaders continually express and bring to bear the central role of culture and spirituality that has driven the vision of Bears Ears National Monument from the very beginning. Tribal leaders aren’t simply advocating for a place they find beautiful or enjoy visiting from time to time. They are giving voice to the land — its plants, animals, waterways, weather patterns — that has sustained their peoples since time immemorial. Bears Ears holds the songs and stories of their past and the seed-in-promise of their future. In that way, the organizing effort around Bears Ears National Monument has been a reaffirmation of identity.

I’ll never forget something that Willie Grayeyes told me on my first day helping out with the Bears Ears initiative in 2014. Willie is the board chair of UDB (Utah Diné Bikéyah) and a Navajo elder and grassroots community leader from Naatsisʼáán (Navajo Mountain). Willie is also a former Navajo Nation council delegate and currently serves on the Bureau of Land Management’s Utah Resource Advisory Council. Willie has long, silver hair that he wears bound in a traditional Navajo bun, a tsiiyéé?, and he is both quick-witted and wise. Our Ute Mountain Ute board members have teasingly nicknamed him gamuch, which means jackrabbit. Willie has been a thought-leader of the Bears Ears initiative since its inception. It was he who articulated that Bears Ears has always been first and foremost about healing. That notion has been an orienting and unifying compass for the entire Bears Ears Coalition throughout the long journey to protect and defend Bears Ears National Monument.

On that first day, I was timid and quiet, listening and observing, not wanting to impose or offend. I had written an essay about the fledgling vision for Bears Ears National Monument, and to my surprise (and mild alarm) the executive director had given copies to all the board members. I remember Willie Grayeyes approaching me late in the day, my essay in his hands. His eyes were on mine, unwavering, as he leaned in and told me, in his signature growl, both fierce and patient, “Don’t be afraid to say it’s spiritual.”

The tribes have never shied away from saying that protecting Bears Ears is ultimately a spiritual journey of healing: healing the relationship between Native peoples and their ancestral homelands, between tribes and the federal government, between people and the Earth. Organizing takes on a whole different feel and purpose when it rises out of the long history and deep spiritual connection that Native cultures and communities have with the land. Such a spiritual orientation cannot be manufactured, nor should it be co-opted. Yet individually and collectively, we all share an inimitable bond with the Earth that sustains us. Starting from that space, and constantly nourishing and returning to it, has made tribes’ organizing approach around Bears Ears uniquely resonant and powerful.

Jill:

Do you see some of this approach reflected in public lands protection efforts in Oregon? If no, what’s a missing piece?

Anna:

That’s a tricky question. I have not been as intimately involved in public lands protections efforts here in Oregon as I have been in Utah (even as an Oregonian!). From what I saw and knew of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument designation effort, as well as the ongoing Owyhee Canyon National Monument initiative — both areas very worthy of federal protection — tribes have not been nearly as involved as the five tribes at Bears Ears, much less in the lead.

That said, a significant facet of recent public lands protection efforts here in Oregon has been the defense of public lands against the armed takeover of Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in early 2016. Perhaps the most potent and resounding response to that bewildering occupation was the Burns Paiute Tribe’s statements on behalf of the 190,000-acre wildlife refuge, which lies within the their ancestral territory. Tribal Chair Charlotte Roderique cogently pointed out the irony of the armed occupiers’ claims to be returning federal public lands to their “rightful owners”: “This is still our land, no matter who is living on it.” Chairwoman Roderique told reporters, “Armed protesters don’t belong here. By their actions, they are endangering ... our sacred sites.”

Chairwoman Roderique’s words rang out across the globe, exposing not only the narrow hypocrisy of the Bundy-esque perception of the commons, but the narrative of settler colonialism that has underwritten natural resource management and allowed the Malheur occupation phenomenon to take root and persist. The Bundys’ rallying cry to “return federal lands to their rightful owners” — i.e. Euro-American ranchers and resource extractors — rings hollow in the face of Chairwoman Roderique’s resoundingly simple statement about true belonging: of people to place, rather than the other way around.

If there’s one piece that’s missing when it comes to efforts to protect public lands, in Oregon and throughout most of the country and the world, it’s this idea of letting tribes lead. Getting out of the way, stepping aside, making room for other voices to rise in their own time and in their own way. Listening: that is the biggest takeaway from the Bears Ears process, and it’s right there in the name — Bears Ears. Native people listened to the land, tribes listened to one another, and the federal government listened to the sovereign tribal nations — for a time anyway.

We’ve got to learn to listen, and not just when it’s convenient or comfortable or happens to behoove our mission or our egos. Rather than approaching tribes and Native communities with ready-made solutions, the first step that the conservation community and mainstream environmental organizations can and should take is to recognize tribes as sovereign nations with complicated modern histories and carefully guarded, highly nuanced traditional knowledge about ancestral ecosystems, organisms and lands. Then organizations that are really ready to be in it for the long haul might patiently seek to cultivate relationships and build trust with tribes. Show respect for tribal protocols and observe tribal chains of command. Be prepared for long pauses. Talk to tribes before talking about tribes. Start by asking, “What do you need?”

Jill:

What would it look like if public lands protection in the West accounted for the U.S. legacy of colonization and focused on indigenous rights and tribal sovereignty?

Anna:

That would look amazing! In fact, public lands are a natural space for such a reckoning to take place, where truth and reconciliation might begin. As ecologist and writer Robin Wall Kimmerer (Citizen Potawatomi) has explained, public lands are ancestral lands after all. Where do we think public lands came from in the first place? Who did they belong to before the National Forest Service or the BLM stuck a sign in them and traced their boundaries on a map? Federal public lands, in particular, are a tremendous seed of reconciliation waiting to sprout.

Under the legal doctrine of the federal Indian trust responsibility, all branches and agencies of the federal government owe a fiduciary duty to every federally recognized sovereign tribal nation and enrolled tribal member. This solemn trust responsibility has been articulated and recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court for nearly 200 years and imposes an affirmative duty of care and loyalty on the part of the federal government toward all 573 recognized tribes and Alaska Native villages. This includes the obligation to protect tribal interests and property.

When we put the two together — the very real fact that virtually all public lands are ancestral tribal territories, alongside the doctrine of the federal trust responsibility (not to mention the perennial underfunding, understaffing, and under-enforcement that federal land management agencies face) — a holistic solution begins to emerge that could help heal the legacy of colonization and honor indigenous rights and tribal sovereignty. What if agencies and administrators charged with managing federal public lands invited tribes to the table and formally engaged the continent’s original sovereigns in helping to oversee and steward their ancestral territories? What if, with the permission and inclusion of practitioners, tribal traditional knowledges began to inform management of America’s public lands? What if tribal co-management of traditional lands and resources was the rule rather than the exception? What if healing historical wounds, inflicted on both people and place, was part of our public lands policy?

That is the vision that was realized through the designation of Bears Ears National Monument, and it’s a model that resonates in our bones and in our bedrock. It also makes sense economically, as the West transitions from a resource extraction economy to a recreation, service and information economy, in which quality of life and climate resiliency increasingly drive decisions about where to live and work.

In this process, tribes have much to teach about renewing humanity’s relationship with the natural world and dwelling in place for the long haul — should we choose to finally listen.

Anna Elza Brady hails from the Olympic Peninsula and has been a lifelong resident of the American West. She has served as co-director of the University of Oregon's Native American Law Student Association and as the policy and communications strategist for Utah Diné Bikéyah, a Native American-led nonprofit, where she supported tribes in securing protection and designation of Bears Ears National Monument. Anna holds a master's degree in environmental humanities from the University of Utah.

View our cardstack to learn more about Anna and the Bear Ears National Monument leaders, here.

MEET THE BEARS EARS NATIONAL MONUMENT LEADERS

Close card stack

The Bears Ears Buttes at sunset with Navajo Mountain (Naatsisʼáán) in the distance. Bears Ears National Monument was named for these distinctive twin buttes, visible throughout the Four Corners region. (Photo by Anna Elza Brady)