Housing Advocates Connect for Justice

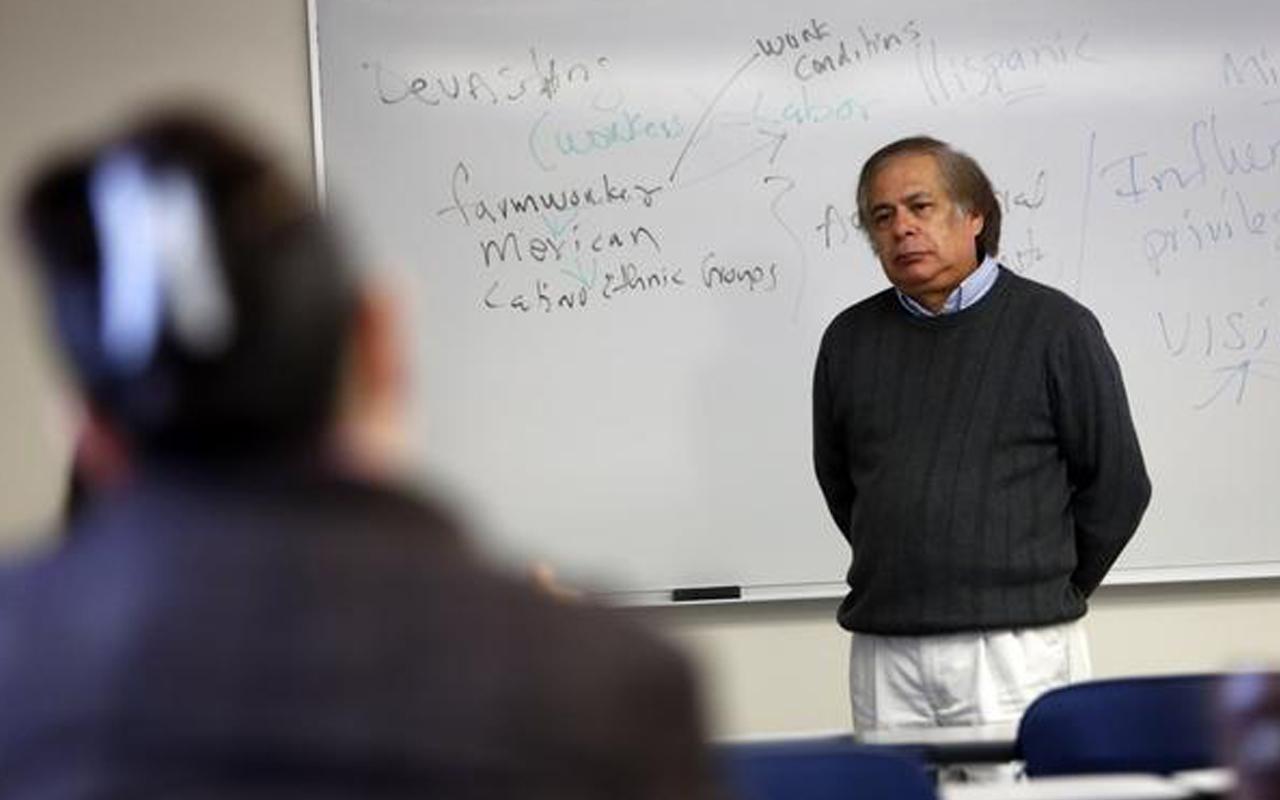

At the end of June, Meyer Memorial Trust gathered an amazing group of 30 housing advocates, organizers and community leaders in Lincoln City for the Oregon Housing Justice Forum. For most of us, it was the first time in over two years we had been in a room full of people we hadn’t met in person before — and in a way that was the whole point. When Meyer’s Housing team started thinking (back in 2020!) about a multi-day gathering of housing advocates from across the state, our central focus was on providing space and time for people to connect, share what they are working on and identify new allies.

COVID-19 has made creating and sustaining relationships much harder for all of us and we knew people were craving an opportunity to step away from Zoom calls and day-to-day challenges to share visions, plans and hopes for housing justice. The last few years have been full of urgent housing challenges, tireless and smart advocacy, dramatic victories in public policy and new resources for housing needs. The forum was designed to serve as an important occasion for advocates to gather together, take a breath, step back and think about what’s next: how do we all contribute to sustaining and growing broad and resilient movements around equitable housing outcomes? We were particularly looking to center the conversation around the needs and priorities of communities of color and to nurture and promote emerging leaders working with those communities and others that have been historically neglected, marginalized and deprived of the ability to secure suitable housing.

In planning the event, we were fortunate to have the help of three savvy and experienced community members active in the field: Julia Delgado from the Urban League of Portland, Jenny Lee from the Coalition of Communities of Color and Loren Naldoza from the Oregon Housing Alliance. Their perspectives and advice as part of the planning committee helped us shape the event, refining the goals and intent, recruiting and selecting participants and the facilitator, I and actively engaging with other participants during the forum.

With the help of our stellar facilitators from the Luna Jiménez Institute for Social Transformation, the planning committee identified five outcomes that guided our approach to the event:

By centering BIPOC leadership, authentic allyship, relationship building, belonging and racial justice, the Oregon Housing Justice Forum will have:

- Increased our understanding of the historical and current impacts of systemic oppression on housing policies, programs, collaborations and initiatives across sectors that lays a foundation for healing from housing injustices.

- Formed a housing justice network (composed of BIPOC leaders, people who have experienced housing insecurities and committed allies) that is relationship-based, expandable, cross-sector and has the potential to become influential and sustainable.

- Reimagined a housing justice ecosystem that launches a bold, inspiring and just housing future in Oregon.

- Co-created key housing justice initiatives that build on past housing justice victories and learning and are designed and shaped by the insights and experiences of BIPOC communities and/or people who have experienced housing insecurity.

- Felt inspired and more prepared to take bold action that fosters relationships and confidence in backing and centering BIPOC leadership and communities in the housing justice space that moves Oregon closer to a vision of housing justice for all.

We decided to limit the size of the event to a group where everyone could engage in the same conversation and connect meaningfully with each other. That meant that we invited only 35 out of the more than 130 people who applied to participate. That roster of 35 was one of the most diverse and dynamic groups of housing advocates the state has ever seen, with notably only about one-third of attendees coming from Portland Metro. All participants brought deep community connections and more than two-thirds identified as indigenous or people of color. Some were familiar to us and connected with current Meyer partner organizations we know well; some were people we had not known of before the event. Core issues and passions represented ranged across the spectrum of affordable housing advocacy, from determined advocates for the houseless to people focused on increasing minority homeownership; from grassroots organizers to people with strong policy expertise to coalition-builders.

Over two-and-a-half days, this extraordinary group dug into the roots of Oregon’s overlapping housing crises, shared their plans, visions and fears around the work in front of them and bonded with new allies in conversations.

Meyer has a long track record of supporting advocacy and organizing work, particularly in affordable housing, and this event was both a natural culmination of that decade-long engagement and a bridge to our new focus built on centering impacted communities, supporting positive systems change and building movements and grassroots power. And the Forum is just the latest chapter in that critical work: we will be engaging with both participants and a wider circle of voices in the next few months to inform how we can support community-driven agendas for housing justice at both the local and statewide levels.

— Michael Parkhurst

Graphic promoting the Oregon Housing Justice Forum