This article was originally included in the Spring 2018 NOLS Newsletter, Published by the Nonprofit Organizations Law Section of the Oregon State Bar. It has been updated slightly for reprint here.

Most nonprofit organizations see foundations as only a source of grants. But foundations have another important, and lesser known, tool for helping organizations with a charitable purpose: Program-Related Investments (PRIs).

Defined in the U.S. tax code, PRIs are investments — including below market-rate loans, guarantees, linked deposits or equity investments — made primarily for an exempt or charitable purpose and not for investment return. They were initiated by the Ford Foundation and MacArthur Foundation in the 1960s, as an alternative way to invest in social change while earning a modest return. Like grants, PRIs count as qualifying distributions toward the 5 percent payout a private foundation is required to make to maintain its tax-exempt status.

What role do PRIs play for nonprofits and for foundations? After spending some time to identify the characteristics that distinguish PRIs from other impact investment tools, I'll explore the reasons why PRIs continue to be a useful tool supporting social change.

The Investment Continuum

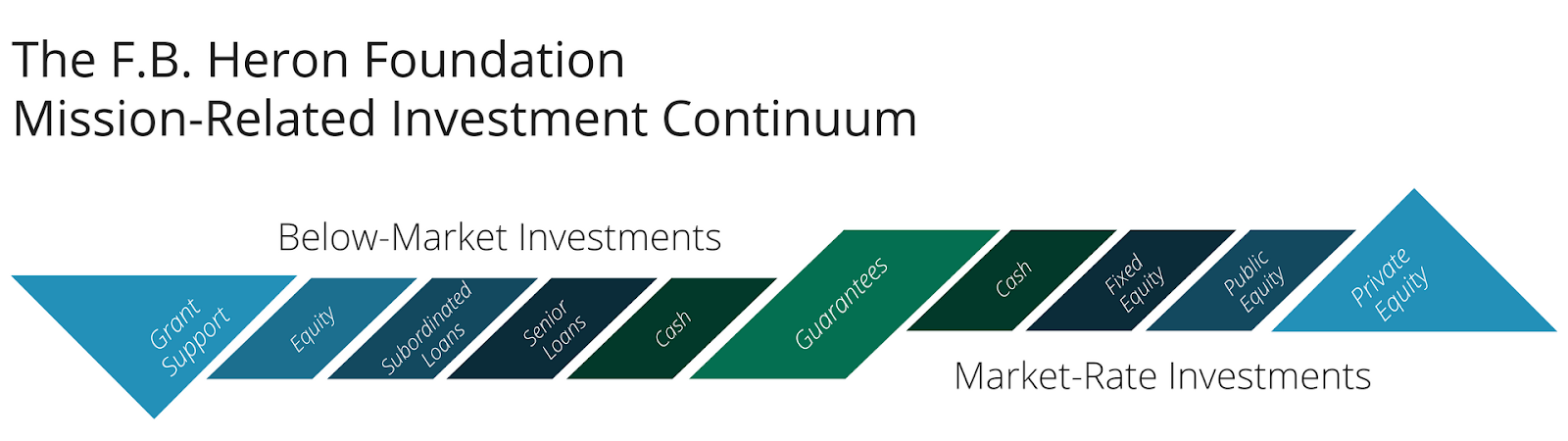

Potential for return is a key characteristic often used to distinguish the range of investments a foundation or social investor may make. At the low end of the return continuum are those investments that have no expected return — grants, in other words. In the middle are a range of PRI options earning below-market returns, and at the high end are more traditional investments earning market rates, such as public and private equity. All come under the heading of mission-related investments because they are made by mission-based organizations, such as foundations.

"Impact investments," another common term, tends to be used to describe a range of investment in companies, organizations and funds while seeking social or environmental impacts alongside financial return. Impact investors are generally seen as broader than foundations and may include wealthy individuals and institutional investors.

As the field of impact investing has evolved in recent years, the push for greater financial return has often overshadowed social and environmental returns. "Too many impact investors have predefined expectations of financial return that are both too high and too short term," wrote the authors of Marginalized Returns, a Fall 2017 article in the Stanford Social Innovation Review, called for a "shift from the false binary of grants with no financial-return expectations, on the one hand, and investments seeking net-15-percent-or-greater return, on the other." The solution? A call for philanthropists and donors to deploy more long-term funding in the form of program-related investments — in essence, refocusing on social impact with lower financial returns.

Meyer's PRI practice

Over the years, Meyer Memorial Trust has completed more than fifty PRIs, and almost all were below-market loans, sometimes coupled with a grant. We've completed both direct PRIs to specific nonprofits and projects and PRIs to intermediaries, such as Community Development FInancial Institutions, that will re-lend to customers. Some examples of PRI loans from Meyer's Award Database are:

- Portland Housing Center - $400,000 (2015) - To increase outreach to underserved homebuyers and to invest in a revolving loan fund for downpayment assistance.

- Cascadia Behavioral Health - $500,000 - To support a project with affordable housing and an integrated health clinic offering mental health, addiction services and primary care

- Craft3 - $4,000,000 (2011) - To establish a loan fund for land trusts to acquire land and secure conservation easements.

In our PRI work, Meyer has used the same program staff to process PRIs and grants, and Meyer typically counts PRIs under its payout budget. By contrast, the market-rate investments are more typically made using foundation corpus funds and lead by investment staff.

Select foundations, including The Heron Foundation, have chosen to remove the division between the investing and the grantmaking sides of the business. In 2011, Heron went "all in" to deploy all of its capital — financial, human knowledge and social — on its mission. One team with wide-ranging skills of financial analysis, investing, research and community-building work in concert to make all investments.

Meyer's functions are not this integrated. We continue to explore intersections of program and investment, and we added a full-time Director of Mission Related Investing to our investment team in 2017. Through our investment team, we are exploring mission-related investments that are expected to earn a market-rate return. Some of these directly connect with and complement Meyer's programmatic priorities, and program staff are engaging in those nexus points.

As of the end of August, 2018, Meyer has $15.6 million invested in PRIs, as well as an active loan guarantee. Although we have paused in making new PRI investments through our recently restructured grant programs, we continue to have a hands-on approach with our 15 outstanding PRIs. Specifically, we have been increasing the duration, flexibility and impact of some of our investments in intermediaries, allowing us to continue to keep dollars circulating in support of mission-aligned organizations and work without impacting our payout. In addition, we are contributing dollars to a pooled philanthropic investment fund alongside other funders, providing opportunities for leverage and efficiencies for both recipients and funders.

Why take on a "Mean Grant"?

Because PRI loans are expected to be repaid, some in the nonprofit field have labeled them "mean grants." That name belies some challenging truths behind PRIs. First, they require a different relationship between the foundation and the PRI recipient. Financial analysis and underwriting can feel awkward when the organization is used to having a grant relationship with a foundation. The organization's board of directors may struggle to understand the different relationship that is being established in a PRI versus a grant and feel intimidated by the PRI documents. There is also pressure to perform, typically reflected in financial covenants.

Structurally, PRIs don't fit every capital need an organization may have. Some projects need a line of credit structure, allowing funds to be drawn down as needed. Many foundations, including Meyer, don't have the bandwidth to manage a letter of credit structure and instead have all the PRI paid out at once. Additionally, foundations tend to invest in shorter projects (1-5 or 7 years) and are not well structured to tie up assets for a 20- or 30-year mortgage in the way a traditional bank lender might. Foundations can also be notoriously slow in processing PRI and grant applications. In a quickly changing market where capital is needed quickly, PRIs are not a great fit.

Despite these challenges, PRIs can still be useful tools for many organizations working for social change. Most foundations make PRIs at higher amounts than grants, so they can play a meaningful part in project financing. As below-market investments, PRIs often have an attractive interest rate (1.5 percent- 3 percent). When coupled with more traditional commercial loans, PRIs can create a lower blended interest rate and significantly lower the costs of capital. Often, they also serve as critical bridge funding in early stages of a project, before an entity may meet the underwriting standards for commercial financing. PRIs can help an organization build a credit history or entice traditional lenders with a guarantee.

From the perspective of the foundation, PRIs also serve many purposes:

- PRIs can complement grantmaking. If a project has a revenue stream that can be used for debt service, a PRI can make sense and be another tool for supporting social impact work.

- By earning a below-market return, PRIs stretch the foundation's corpus to allow for more resources toward mission and social change. By our calculations, PRIs have allowed Meyer to grow the corpus by $25 million in the last few decades.

- PRIs can buffer the foundation's market-rate investments. During the Great Recession of 2008-14, PRIs were, for some quarters, the second best performing asset class for Meyer Memorial Trust.

- PRIs allow an easier way to invest in a broader range of entities, including for-profit corporations that advance its social goals. Meyer made its first PRI to a for-profit entity that developed a biomass system using waste wood to heat public buildings in Harney County.

- When done in larger amounts, PRIs serve as an efficient way to meet a foundation's payout.

Despite some challenges posed by PRIs, they serve an important role by being a flexible, capacity-building tool for mission-related investments for social change. Many private and public foundations are wading into the PRI space, either by experimenting with a few solid PRI candidates or launching more robust programs. It's safe to say that PRIs will continue to be a critical tool for philanthropy and social impact well into the future.

–– Theresa