We will never forget spring 2020. The impact of and response to the novel coronavirus has been simultaneously saddening, enraging and inspiring. We are seeing heart-wrenching losses and immense health and economic fallout. We are being inspired by front-line workers who put themselves at risk to take care of the sick and keep essential services moving. People are adapting, innovating and showing kindness in so many ways. We are also coming together in one of the biggest collective actions ever by physically distancing ourselves from each other in an effort to stem the spread of the virus.

What’s also crystal clear is that although COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, is harming all communities, communities of color are the most impacted. A study released last week found that COVID-19 patients exposed to even a moderate increase in air pollution long term are at a greater risk of dying. Black Americans are dying from COVID-19 at higher rates partly because they disproportionately live in places with more air pollution. On Friday, Race Forward, which has a mission to catalyze movement building for racial justice, summed it up: “Let’s be clear: Coronavirus kills, and structural racism is its accomplice.” This is because the systems and structures that drive how our society operates in a pandemic are the same broken systems that drive how it operates in normal days.

At Meyer, we understand this. We know that structural, institutional, historical and systemic racism are components in the context in which we do our work. We also know that the exploitative mindset that underlies structural racism is the same mindset that drives and sustains the overexploitation of nature. Dominance of people and nature is the story of our nation and of Oregon.

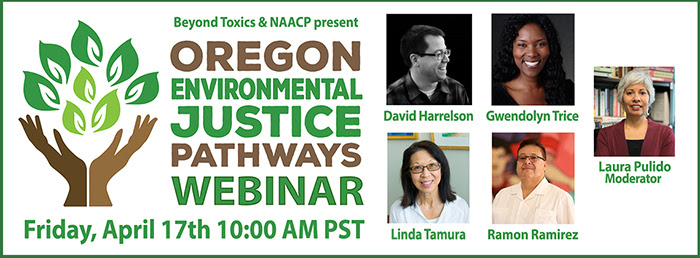

Organizers of the Oregon Environmental Justice Pathways Summit postponed the in-person convening until fall 2020. However, the organizers decided to host a virtual summit “teaser” last week by engaging some of the speakers to share a preview of their presentations on what would have been the summit’s opening day. In honor of Earth Day 2020 and to elevate the need to strengthen and grow Oregon’s environmental justice movement, I wanted to share some highlights from the preview.

University of Oregon Professor and Ethnic Studies Department Head Laura Pulido moderated a 90-minute webinar on Oregon’s environmental justice history that included the following speakers.

In the opening presentation by David Harrelson, entitled “The Kalapuya and the Myth of Wilderness,” David spoke about the history of the Kalapuya people’s cultural management of their ancestral territory in the Willamette Valley since time immemorial. He also explained how one of our country’s core conservation laws, the Wilderness Act of 1964, has played a role in building the narrative around the idea of “pristine nature without humans” that is grounded on the removal of Native American people and has informed how conservation has been practiced in the United States.

He reminded us that the cultural practices of the Kalapuya people have shaped their ancestral lands in northwest Oregon for more than 500 generations and that there is no “untrammeled land” — a term from the Wilderness Act — in their traditional territories. This narrative of pristine nature and the practices driven by it have invisibilized the Kalapuya people’s history and created barriers to their ability to practice traditional cultural management of the land today. David noted that he sees the opportunity to learn from, understand and translate ancestral teachings about land management to have a much more holistic and resilient management regime in the future.

Gwendolyn Trice’s presentation “Oregon Timber Culture: Then and Now” opened with the story of Black loggers from Maxville, who were recruited to move to Oregon to work in the timber industry at a time when the Oregon Constitution prohibited Black people from residing in or owning property in the state. Gwendolyn shared how the Black families in Maxville lived in segregated housing, attended segregated schools and played on a segregated baseball team, as well as greatly contributing to creating a vibrant timber community.

She talked about the significant role of the Ku Klux Klan in Oregon in the early 1900s, describing it as the the biggest social club in the state that played a key role in connecting the dominant culture at the time. It also played a prominent role in Oregon politics. Gwendolyn also talked about Vernonia, another small timber community, as a place where different racial and ethnic groups lived and worked in segregated and substandard conditions until the NAACP stepped in to advocate for improvements. Beatrice Morrow Cannady, who was the first Black woman to graduate from law school in Oregon, was a key leader in this movement.

Ramon Ramirez grounded his presentation about Oregon farmworkers in the history of the agriculture movement in the U.S., which is rooted in exploitation that began with slavery and shifted to the sharecropping system and now excludes farmworkers from national labor laws, which were first passed in the 1930s.

Ramon shared that 70% of the farmworkers who work for piece rate in the Willamette Valley are members of undocumented and Indigenous communities. Their exclusion from labor law protections, poor living conditions and legal, but dangerous, industrial agricultural practices expose them to significant health risks. Ramon shared startling information gathered from a Marion County clinic that over half of the farmworker women they serve have had miscarriages. He also shared that the average life expectancy of a farmworker is 49 as compared with 78 in the U.S. and that 25% of farmworkers get cancer.

He ended his comments by highlighting the brutal reality that even though farmworkers are deemed “essential workers” during the coronavirus crisis, most of these workers will not be able to access benefits from the recently passed CARES Act because of their citizenship status.

Linda Tamura shared how Japanese immigrants came to Oregon and how racism impacted the Japanese community for generations in the state. Japanese workers were drawn west to work on the railroads’ expansion. In the early 1900s, a strong community of Japanese immigrants grew in Hood River and gained property in exchange for clearing land for white property owners. They grew strawberries and asparagus, while establishing apple orchards.

Linda recounted how after a number of attempts, Oregon passed an Anti-Alien Land Law to prevent Japanese immigrants from purchasing land in 1923, which Japanese families were able to subvert by buying land in their children’s names. In 1942, the U.S. passed Executive Order 9066, which led to the forced removal of the Japanese community from Hood River and imprisonment in concentration camps during World War II. Many Japanese families had to abandon their businesses and personal possessions during this period. Some lost their land. After the war, parts of the Hood River community did not welcome the Japanese community’s return and tried to prevent families from returning to land they already owned.

The remarks and reflections of the speakers threaded together pieces of the history of structural racism in Oregon and its intersection with our relationship with nature today. There’s much more to unpack from this history. Understanding our shared history is an important part in addressing environmental justice issues and ensuring that all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, gender identity or expression, income, or citizenship status are able to access a clean and healthy environment where they live, work and play.

I encourage you all to tune into the full 90-minute presentation and join me in the fall at the Oregon Environmental Justice Pathways Summit.

— Jill